εἰ δὲ ὀρθῶς εἰκάζω, τὸν Εὐαμερίωνα τοῦτον Περγαμηνοὶ Τελεσφόρον ἐκ μαντεύματος, Ἐπιδαύριοι δὲ Ἄκεσιν ὀνομάζουσι.

If I conjecture aright, the Pergamenes, in accordance with an oracle, call this Euamerion Telesphorus (Accomplisher), while the Epidaurians call him Akesis (Cure).

Pausanias 2.11 (LOEB)

A single space and the things standing within can have a variety of meanings, depending on the visitor. Churches and their art, for example, can be a focal point for religious ritual and serve as touristic attractions simultaneously. The reason for a visit results in different activities, traces and narratives of these visitors at the site. Together these elements create a complex sacred space that is constantly under construction and negotiation. Similarly, in the past, sacred spaces could attract a wide variety of people for different reasons and with different intentions. This is certainly true of sanctuaries of the Greek god of medicine and healing Asklepios. The description of Pausanias cited above of only one statue in the temple of Asklepios in Titane reveals that objects in Greek sacred space that might look the same, i.e. Pausanias reflects on the imagery and connects it to various names, could be interpreted in different ways. Space and everything standing within it can thus have a variety of meanings created by multiple voices (i.e. the actors) that can be found within ancient sacred spaces. In order to understand Asklepieia, and Greek sanctuaries more broadly, we need to understand the multiple voices we can detect within them and the complexity of their attitudes towards sacred space. This multivocal approach ascribes agency to many different actors, enabling us to consider sanctuaries as lived spaces constantly being shaped through a multitude of actors and actions.

Sacred space is a complex conglomeration of many users and types of activities. How can we understand sacred spaces if we only study parts of these various users and activities in isolation from each other? These different layers do not operate in isolation and should be researched together in order to achieve a holistic understanding of sacred spaces. My study focusses on sanctuaries for the Greek god of medicine and healing, Asklepios, during the Hellenistic period. Various elements of Asklepios worship and various types of sources are now scattered between studies, but have to be brought together and analysed in relation to each other to understand the Asklepieia and its various layers. One might argue that this has been made obsolete by the large studies of the Edelsteins, Riethmüller and Melfi that together encompass most sources. Nevertheless, even in these studies roads towards new interpretations remain open, due to choices they made: focussing on literary sources (Edelsteins), focussing on buildings (Riethmüller) or emphasising similarities and the healing role (Melfi). Furthermore, new approaches to Greek religion and sanctuaries have opened new avenues to re-interpret existing material.

Within scholarship regarding Asklepios, in general there are three overarching trends when dealing with Asklepios: a focus on healing, an emphasis on similarities between cults and sanctuaries of Asklepios and a focus on supraregional visitors of primarily the larger sanctuaries. In the discussion in the historiography another overarching element is visible: Asklepieia are generally approached from isolated perspectives – either one type of source or one aspect of the sanctuaries – resulting in an incomplete picture of the various roles and audiences these Asklepieia attracted and especially their interaction. Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis (2010) in her work on the Pergamene Asklepieion can be quoted to illustrate the necessity of bringing the varied material together and that avenues for re-interpretation are still possible: the “material is not new, but has until now been examined in isolation. One of the major reasons for this lies in the entrenched division between Classical literary and archaeological disciplines.”

Previous studies are fundamental, but also adopt a narrow focus, which essentializes these sanctuaries, overlooks the varieties of agencies, downplays the overlapping functions of sanctuaries, and fails to address their complexity in a satisfying way(See Scott 2010 for a similar problem regarding Olympia and Delphi). Yet this complexity is crucial for their understanding. Rather than projecting selective patterns, we need to study the interplay and competition of all the available elements found within sanctuaries. An important role is left for the users: they activate the specific role of the sanctuary they require (e.g. social, political, religious or economic), but their agencies are to a degree determined by structures such as social rules. A synthesis of elite and non-elite activity is furthermore fundamental towards understanding the dynamics of sacred space. Moreover, human and non-human agents (e.g. visitors, objects and architecture) should be assessed in relation to each other, rather than as isolated phenomena (Haug & Muller 2020, 13)

The research objective is to understand the social complexity of centres dedicated to Asklepios. The focus is on the different audiences of Asklepieia and specifically their agency and experiences in relation to the Asklepieia. Who were involved at the sanctuary, where did they come from, what did they want, what traces did they leave behind, and how did these influence each other? How did Asklepieia function for different groups of people? How did Asklepios become part of the lives of individuals, social groups and of entire polis communities? Essentially, this research brings together the various layers that comprise the Asklepieia and tries to understand their interrelationship in order to give new insights into the dynamics of creating complex sacred spaces. Placing the users central help with understanding how “those who inhabit the space give it meaning” (Eidinow 2020,192).

Cases-studies

Instead of opting for a full-scale study and collection on Asklepios across all regions, in line with Riethmüller’s study, I shall focus on a selection of Asklepieia in mainland Greece and the Aegean, more in line with Melfi’s approach. The main reason being that the focus is on the approach and new insights these will give on Asklepieia and Asklepios. Moreover, I believe a “grand-narrative” on the sanctuaries of Asklepios is not the ultimate goal, if possible at all. Instead, it is the contextualization of what these sanctuaries meant and what needs they fulfilled for different groups of people in various poleis that is the objective.

Several criteria were used to choose the cases: 1) they must provide literary, epigraphical and archaeological sources; 2) they have to represent multiple locations in relation to the polis they belong (i.e. inside the city, close to the city, extra-urban; 3) they must represent multiple regions in Greece.

The chosen sanctuaries are located in different places in relationship to the polis. Mainland Greece and the Aegean are chosen due to their categorisation by Melfi as a culturally uniform region, whilst I do believe insights can be gained by also looking for differences between Asklepieia (Melfi 2007, 12). On a more practical level, most excavated Asklepieia are located in mainland Greece and the Aegean based on Riethmüller’s catalogue (Riethmüller 2005, vol.1 76; vol.2 for the catalogue). Moreover, the sanctuaries in mainland Greece are relatively old and various regions under study had their own mythologies of Asklepios.

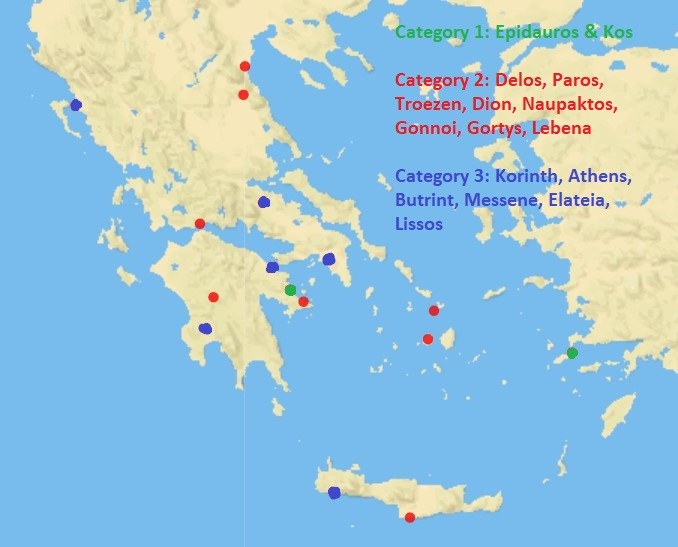

The selection of case-studies includes sanctuaries of different sizes and in different locations in relation to their cities. They are divided into three categories as a means to structure the thesis. The first category comprises supraregional sanctuaries (category 1), specifically Epidauros and Kos. These sanctuaries provide a large variety of data and are thus a good starting point for this research. Sanctuaries of regional and local importance include: Dion, Gonnoi, Elateia, Naupaktos, Messene, Gortys, Butrint, Troezen, Athens, Paros, Delos, Lebena and Lissos. These are divided into extra-urban (category 2) and urban (category 3) sanctuaries, in order to detect any differences in function, audience or scale between sanctuaries within the urban center and those outside the core.

The scopes used in the thesis are to a degree arbitrary, but are required as a structuring mechanism of the final manuscript. The label supraregional does not mean that Epidauros and Kos will be researched by only looking at the supraregional level. As a matter of fact, I believe this has been done too much and such a point of view limits our understanding of the sanctuary by downplaying the local and regional importance/functions of the sanctuaries (Schievink 2022). However, in contrast to the Athenian Asklepieion, for example, these two did have larger supraregional attraction (Aleshire 1989). Similarly, the more regional and local sanctuaries are not only regional or local. To illustrate, the Asklepieion of Delos attracted Rhodians and Phoenicians (IG XI, 4 1133; ID 2322). Nevertheless, in contrast to Epidauros or Kos the amount of supraregional attraction of this Asklepieion is limited. It is the interaction between local, regional and supraregional levels and influence on each other that is moreover fascinating and important.

Some important omissions are clear, for example Trikka or Pergamon. Trikka might be included if a sanctuary of Asklepios there were to be clearly identified (The Municipality of Trikka wants an excavated site in their city to be an Asklepieion https://trikalacity.gr/en/building/asclepeion-ancient-trikki/. Yet this is disputed, see Riethmüller 2005, vol.1 93-98). Other omissions like Pergamon are due to the data: most published sources related to the Pergamene Asklepieion are from the Roman period (Riethmüller 2005 vol. 2, 632-634; new research is exposing the Hellenistic shrine, and the Asklepieion may be used for comparative purposes where relevant. See: C.G. Williamson, Deep-mapping sanctuaries. Mapping experiences at festival hubs in the Hellenistic world http://deepmappingsanctuaries.org/). But more importantly, it is not my aim to understand all Asklepieia. This risks creating a uniform narrative on his cult(s), whilst I want to understand how complex sacred spaces are continuously created through the agency and experiences of different social groups.

Method – interpretative framework

A selection of approaches can be utilised to give insights into the complexity of Asklepieia. This research starts with placing the (multiple) users and how they used and experienced the sanctuaries central; a multivocal approach. Multivocality is an archaeological approach that introduces greater inclusivity (in the present) to site interpretation, drawing on a variety of perspectives and experiences (e.g. Rodman 1992; Hodder 1997; Hodder 2008; Shillito 2017). This approach can be applied to the past, where also different perspectives and experiences towards the same spaces can be detected. However, simply stating who was there is insufficient to create new insights into the Asklepieia; or as Hodder says regarding modern multivocality: it “involves a lot more than providing a stage on which they [marginalized groups in Hodder’s case] can speak” (Hodder 2008, 196). What is fundamental is to gain insights into the agency of the various users, with taking into account that some had more agency than others, learn about how different groups of people might have experienced sacred space depending on their motivation to go into the sanctuary and lastly how space is constantly created by these voices in different ways over time. In order to do so, Lived Ancient Religion (LAR), Spatial Studies and Memory Studies are chosen as theoretical frameworks.

LAR

Agency of various users can be brought to the foreground using Lived Ancient Religion (LAR), a relatively recent interpretative framework on ancient religion highlighting the plurality of the topic ancient religion (For an introduction see Gasparini et al. 2020, but also Raja & Rüpke 2015; Rüpke 2016; Rüpke 2018). Conflicting or parallel (ritual) activities within the same sacred space can be better contextualized using two of the pillars of LAR: appropriation and situational meaning of sacred space and rituals. Can we find evidence of people neglecting ritual norms, or are there patterns of behaviour attested archaeologically that might not fit with the expectations of ritual healing practices? Do we see different groups of people using the sanctuary in different ways simultaneously, thus appropriating the required need and establish a situational specific meaning? How can that help us give insights into the meaning of these spaces?

Space

Users of sacred space operate in a demarcated space shaping how they could use the sanctuary, whilst also in turn these users impact sacred space itself (Van Andringa 2015, 37; Haug & Müller 2020). Spatial Studies, both analyses on the physical space, but also the social and mental aspects of space, helps to analyse the role space plays for various users. This includes the architectural setting, the statues and inscriptions displayed in the sanctuaries under study and the open spaces available to the worshipper; these could guide movement, distract the worshipper or attract specific types of activities (e.g. Connelly 2011 on open spaces; Chaniotis 2012a-b and Martzavou 2012 on inscriptions; Ma 2013 on statutes; Müller 2020 on switching between open/closed-off spaces; Wescoat et al. 2020 on interstitial space; Williamson 2021, 55-58 on transitional zones, linear space and spatial syntax; Scott 2022 on temenos-walls). The mental aspect of space primarily concerns how space is created in the mind through circulating narratives and myths about the space, which impacts the potential experience of visitors but also creates a sacred space in the minds of those reading or hearing these narratives without necessarily going to the sanctuary itself (Wortham-Galvin 2008).

GanMed64, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Memory

Lastly, there is an element of time involved in this research that will be analysed using memory studies (Halbwachs 1992; Connerton 1989). Objects stored within sanctuaries, narratives about the sanctuary and the architecture of the sanctuary itself impacts later generations (On memory-studies in antiquity see Alcock 2002; Alcock & van Dyke 2003; Price 2012). Physical construction of sacred spaces, as well as the layering of ritual practices, creates the a temporal framework in which action takes place for long after the construction itself. Memory studies are primarily useful when reconstructing the impact of objects and narratives on the experience of later viewers, as well as contextualizing the role of the sanctuary for various groups of people over time (On the role of narratives see Kindt 2016; Eidinow 2020).

Opportunity

I believe the above frameworks help to better understand the co-existence of multiple groups of people inside the Asklepieia and their relationship to each other. It helps to give agency to a larger group of people in continuously constructing sacred spaces and give insights into the experience of these visitors ultimately contextualising the social complexity of Asklepieia; what did these spaces mean for people in the past?